Outside was a preposterously beautiful, Technicolour autumn day, all blue skies and trees turning the colours of fire. If you’d used it in a film it would have been for heartbreak and parting, a belated outpouring of summer made all the more vivid because it is nearly time to say goodbye. Inside the grand but compact chamber of Henley’s Town Hall it was unseasonably warm; with five minutes to go there were only two seats left, and I took one of them. ‘Not much knee space. We’re rather close,’ somebody said as I squeezed in and arranged myself.

Outside was a preposterously beautiful, Technicolour autumn day, all blue skies and trees turning the colours of fire. If you’d used it in a film it would have been for heartbreak and parting, a belated outpouring of summer made all the more vivid because it is nearly time to say goodbye. Inside the grand but compact chamber of Henley’s Town Hall it was unseasonably warm; with five minutes to go there were only two seats left, and I took one of them. ‘Not much knee space. We’re rather close,’ somebody said as I squeezed in and arranged myself.

We were a packed and anticipant roomful of mostly women, book lovers and therefore by definition fond of the essentially private pastime of reading, though we were there not to read but to listen and to ask questions, to experience fiction as a public event. Instead of words on a page or a screen, we were going to see the writers who had drawn us there and hear their voices. We wanted stories, but more than that, we hoped for a glimpse into how and why they were told.

At one end of the room was a small and empty stage with three important-looking chairs, which were throne-like but in the manner of an English town hall and therefore designed for the comfortable sitting-out of long meetings as well as to be imposing. I imagine all sorts of practical things have been discussed in that room over the years: the price of corn or parking, the collection of refuse, the balancing of books and the taking of votes.

We weren’t there for any of that. We were there for semen and baby shoes, tales of a psychopathic rapist or a leech-like friend, families divided by wars and continents and the brutal convictions of an era, the tragedy of failed reconciliations and the power of impossible loves. And that was what we got, but as if that wasn’t enough, we also got to find out a little bit about what it takes to make all that stuff up and write it down.

Secrets uncovered: the prelude to post-lunch erotica

Windows were opened; the noises of outside – traffic, the market – drifted in along with the stirring of cooler air. A frisson ran round the room as our writers came in and went up to the little stage and took their places. We were on our way.

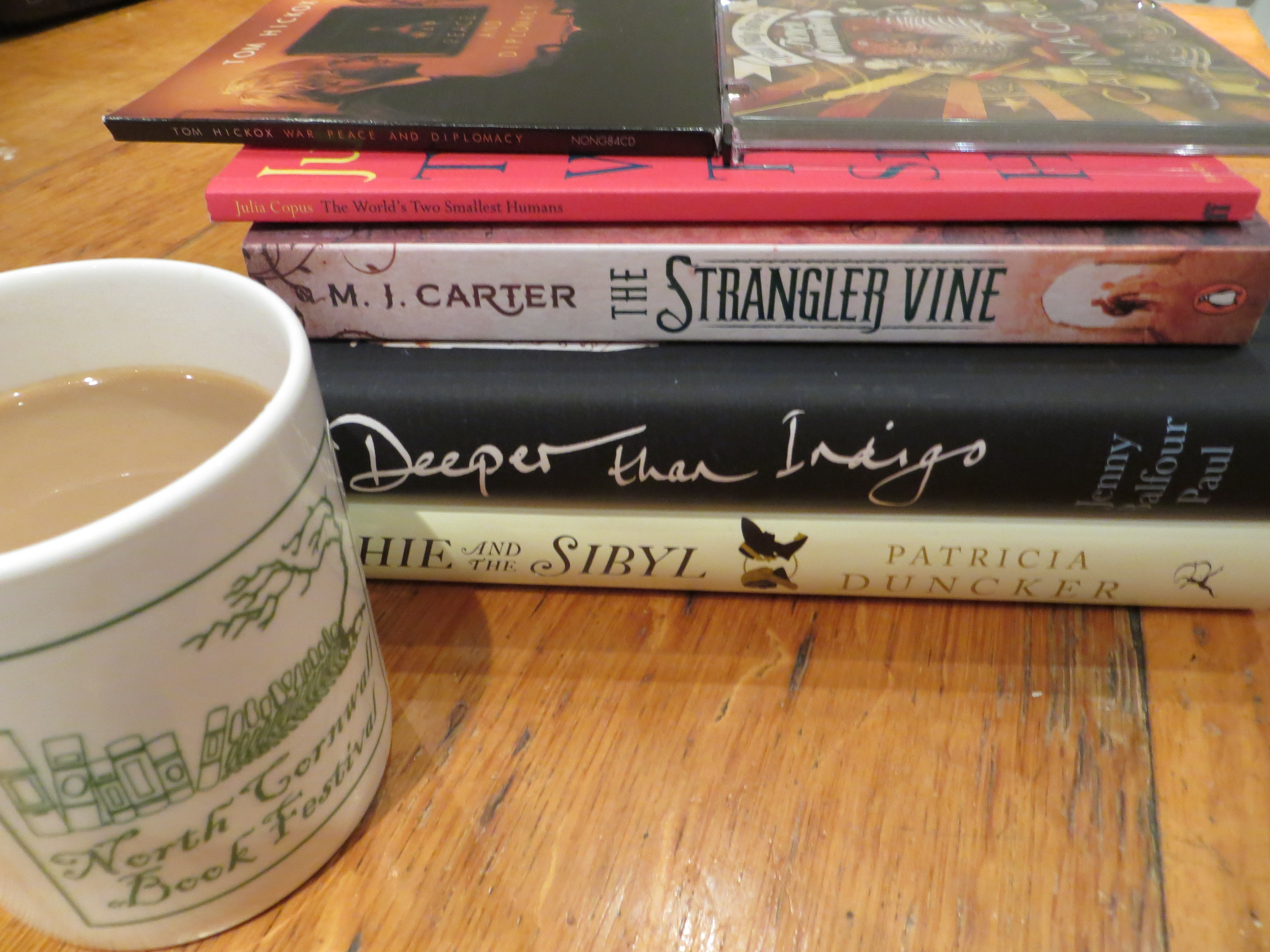

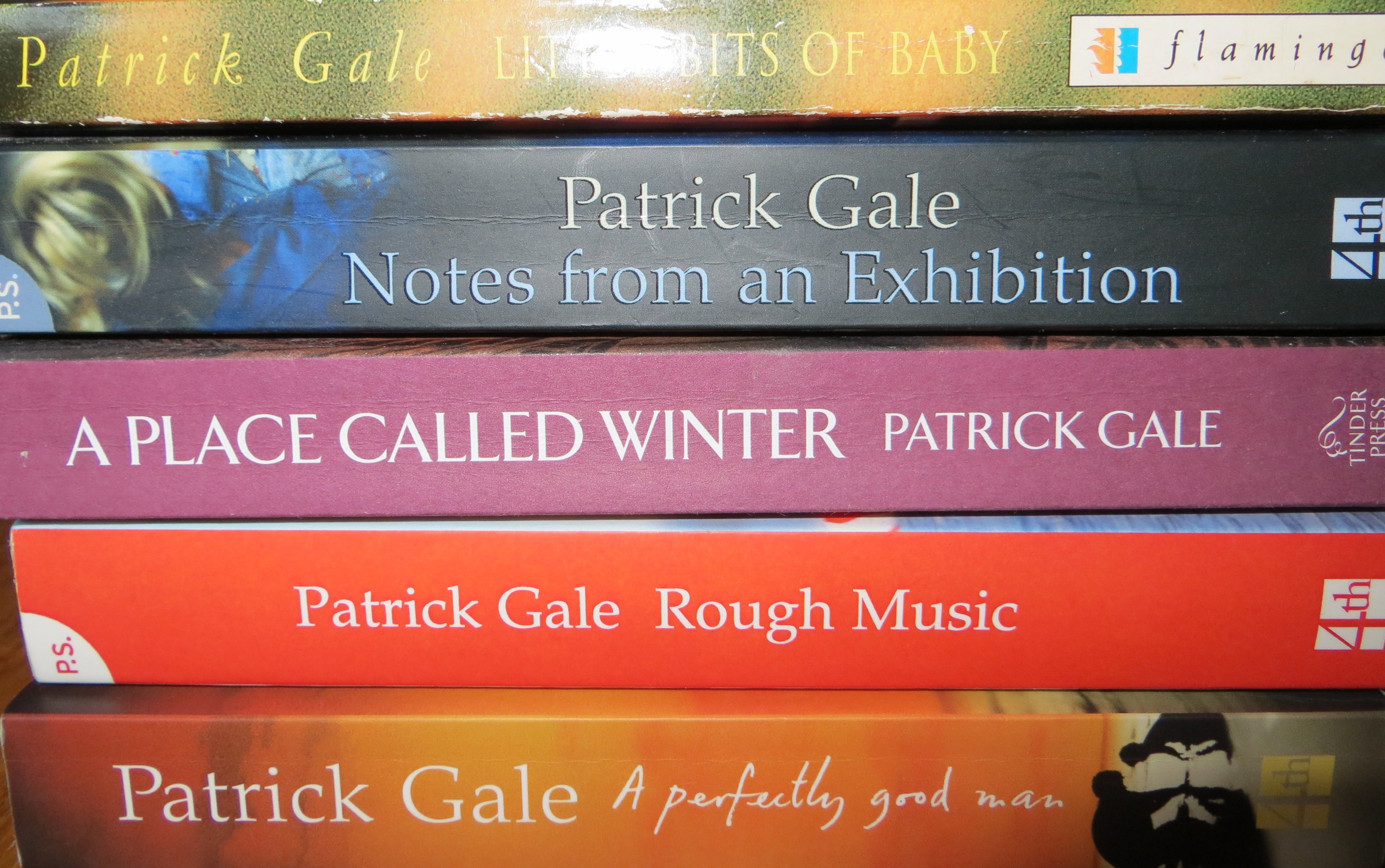

I’m sorry not to have a picture of them: they were a glamorous pairing. Patrick Gale is a dazzlingly charming silver fox, with a voice you could listen to forever – I think I’m right in saying he wanted to be an actor when he was younger and he has that gift that some actors have of making an instant connection with other people, a sort of receptivity that both gives and holds attention. I’m onto my fifth Patrick Gale novel now and am a committed member of his fan club, or would be if he formally had one. If you haven’t read any, and you have a space in your reading life for a writer who will draw you in, make you care, make you laugh and break your heart, then go get started.

Polly Samson was new to me. There’s something otherworldly about her which makes it not quite right to describe her in worldly terms. She’s beautiful, poised, measured, with the kind of cool intelligence and self-possession that suggest heat under the surface. She’s also kind of rock’n’roll. She’s a lyricist as well as a novelist; her other half is David Gilmour from Pink Floyd and when she’s working on a book she reads what she’s written each day out loud to him in the evening.

Our hour with Patrick and Polly was hosted by Lucy Cavendish, who mentioned that Polly hadn’t eaten any lunch while Patrick had got through two chocolate brownies. If he was skittish, so were we. Off we went with a discussion about how both authors’ latest books had drawn life from their family history and secrets. Patrick told us about Harry Cane, his mother’s mysterious cowboy grandpa who emigrated to Canada under something of a cloud. Patrick set out to tell a story that would explain both what had happened to him and the way the family spoke about him, ‘a story that the women of the family wouldn’t have been told, but that might have been true’: ‘my nefarious scheme of gaying my great-grandfather.’ (I think that might be my favourite PG line from the session, along with the description of the readings as ‘post-lunch erotica’.)

Polly relayed a story from her own family history, a tormenting love triangle in which paternity was at stake. A couple who could not have a baby asked a friend to father a child for them, which he duly did before emigrating to the US, with the understanding that future contact between them would be minimal. But then war broke out and the husband sent his wife and child to their biological father in the US for safety, remaining in Paris to sort out paperwork… and ended up interned and separated from them for years, after which time his wife had decided that their child only needed one father, and was already living with him. A terrible story which culminated in the husband’s suicide.

This fed into Polly’s new novel The Kindness, though transplanted into a different time and place. Polly’s own complicated parentage also provided fuel for the story, and she told us about the father figure with whom she had lost contact, who she later learned had kept her baby shoes close by all his life.

A lesson in how to breathe and a cloudy offering

Both writers read aloud from their novels. Both read scenes that involved seduction, of one kind or another. Polly’s had a specimen jar, innocence yielding to scientific curiosity and a braless milkmaid, the examination of a cloudy offering. Patrick’s had a therapist who teaches a young man to breathe, then introduces him to sex on a bed so narrow that one of them must always be on top of the other. Clients visit in the morning, but the young man is invited to return in the afternoons: ‘You can just wait in the bed.’

We laughed and fanned ourselves with the useful cards explaining who had sponsored the event. They had us. We were sold. Now we wanted to find out how they had managed it. And this is what we learned.

(Warning: there are some spoilers in what follows, though I’ve tried to keep them to a minimum, but if you absolutely hate spoilers, you should go and read the books first. If, like me, you are undisciplined and sometimes even peek at the end of a story before you get there, you won’t care.)

The novel you end up writing may be quite different, in form at least, from the one you set out to write.

This was a bit of a revelation to me as I thought it was only me that did this and everybody else just put together their card indexes or flow charts or whatever and wrote the damn things, but no.

Patrick set out to write a very simple book, drawing on EM Forster and boys’ adventure stories, starting at the beginning and rattling on to the end: wrote it, and then set about chopping it up, both to tease the reader through the narrative and to break up the sadness in it. So the novel is a bit like a thriller, in that you learn early on that Harry has killed someone and that there are loves he can’t speak about.

Polly’s last book was a collection of interlinked short stories, and she set out to write this one as a series of stories but then restructured it so that she had two main voices followed by a third voice. She had been surprised by comments that it was like a thriller, and hadn’t set out to write a novel with twists and turns, but there they were. This meant she’d had ‘the joy of writing from two perspectives’ – she gave as an example an assignation in a Paris hotel described from the point of view of both the male and female lover, a fantasy made real for one and a seedy compromise for the other.

The story will be brought to life by the happy accident of characters who make their own way in.

Patrick told the story of Troels Munck, the antagonist to Harry Cane’s hero and, for my money, one of the most terrifying and convincing villains in all of literature. (A Place Called Winter is revelatory about evil, and how people try to survive it and can be destroyed by it.) The name was given by a real-life someone who had won an auction for it to be included. Patrick described the email exchange that followed: (PG): ‘Is it all right if I turn you into a psychopathic rapist?’ [LONG TUMBLEWEED EMAIL SILENCE] (TM): ‘OK, as long as he is hot.’

Is Troels hot? He’s a bully and a brute, but a compelling one – and he’s real, which is testament to the truthfulness with which he has been created. God save us all from encounters with the likes of Troels – outside of the pages of a book.

Polly spoke about Katie, the leech-like friend who was meant to be just a line in The Kindness but kept turning up. She also described the intense absorption of writing, how her children would come back from school and talk to her about their days and she would find herself not really taking it in, still caught up in the world of her characters. (I know that particular daze.) But she’d read Elena Ferrante while she was working on The Kindness – four years of close work, twenty years of gestation in all – and had found that Ferrante’s characters were as real to her as the ones she had invented herself and was carrying round with her. (Now I have to decide what to read next, The Kindness or Ferrante.)

Polly commented on how characters seem to turn up fully-formed. Patrick agreed: ‘They have to be, or they don’t work on the page.’

But what about planning? Patrick said he plans meticulously, but then ignores the plan. ‘It’s like getting ready for a play – I need to know about the characters and feel confident about who they are.’

The land you put into your book will shape it.

Patrick explained how as he worked on the book he had got increasingly angry about what had been done in Canada, but had wanted to show that in an elliptical way, without tub-thumping about imperialism. It’s there in the tragedy of Ursula. Also, as he explored the landscape and the history of the settlements, he became increasingly aware of how dangerous it was, and how vulnerable his characters were. Hence Troels.

Here’s a surprise nugget for you: there were no starlings in Canada till 1934, as a Canadian friend of Patrick’s told him after reading an early draft. Starlings follow agriculture and it took till then for them to arrive. So you won’t find them in Winter.

Patrick talked about his road trip to find his grandfather’s lot, and asked Polly if the house and garden in The Kindess were based on a real place: ‘I really wanted to go weeding there.’ Polly said the garden was a mixture of gardens she had loved.

Inevitably, your research will shape your book. Are there starlings, or not? Polly’s novel opens with a hawking scene. What size are the baby mice fed to a hawk?

Children in stories – yearned for or lost – exert a special power.

Harry Cane is a father, separated from his child by both distance and disgrace, and the plot of The Kindness hinges on the fathering of a child. Patrick said he felt that the male yearning to be a father is not much written about, and I think this is true; as he said, most stories that touch on this cast the father as the reluctant figure and the mother as longing for a child. (There is a weird nexus of cultural confusion around this, a mixture of blind spot and acute sensitivity – writers, take note: when that happens, there’s something to dig for.)

The story of Polly’s baby shoe lingered with us. (It made me think of the design for the hardback cover of Julie Cohen’s Dear Thing, which featured baby shoes, and which prompted a brilliant baby-shoe-shopping scene in the final version of the book.) At the end of the session, when I was chatting with my neighbours in the audience, one of them mentioned Ernest Hemingway’s potent six-word story: ‘For sale: baby shoes, nearly worn.’

And finally…

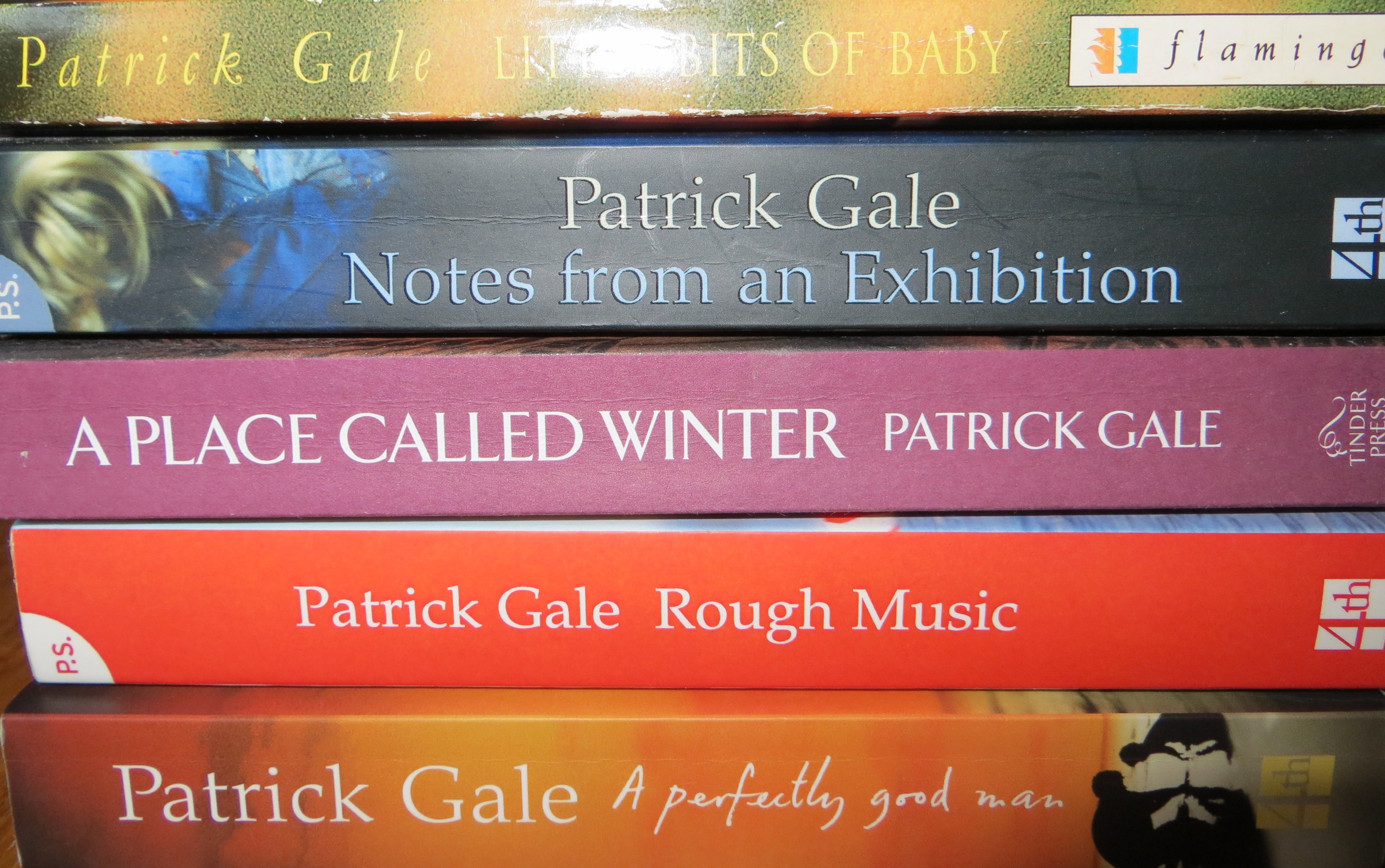

Patrick was asked whether he had a favourite out of his books. And yes – he does: they are the ones he wrote during the happiest times of his life: Notes from an Exhibition, Rough Music, Little Bits of Baby. ‘I’m always very protective of the most recent one, it’s like a child that’s just started school.’

And then we were done. We shifted and stretched, murmured to each other about how good it had been, formed an orderly line for books and signing, began to slip away.

Sooner or later we will start to read. We will hear those stories again, not in the august surroundings of Henley Town Hall but wherever we are – on a lunch break, in an armchair on a winter’s night, in the doctor’s waiting room. And once more we will allow those voices to take us somewhere else.

Polly Samson and Patrick Gale were speaking at Henley Literary Festival, in conversation with Lucy Cavendish, at an event sponsored by HW Fisher & Company.

like maybe the seaside

like maybe the seaside